Marwan Barghouti

Marwan Barghouti | |

|---|---|

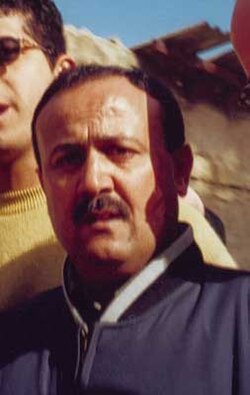

Barghouti in 2001 | |

| Member of the Palestinian Legislative Council | |

| Assumed office 1996 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 June 1959 Kobar, Jordanian West Bank |

| Political party | Fatah (before 2005, 2006–present) Al-Mustaqbal (2005–2006) |

| Spouse | Fadwa Barghouti |

| Children | 4 |

| Palestinian nationalism Factions and leaders | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Map: Birthplaces or family origins Details below: p. parents from, b. born in, d. death. |

||

|

| ||

Marwan Barghouti (also transliterated al-Barghuthi; Arabic: مروان البرغوثي; born 6 June 1959) is a Palestinian political leader.[1][2] An elected legislator and an advocate of a two-state compromise with Israel, he has been imprisoned by Israel since 2002.

Barghouti led street protests and diplomatic initiatives until the early Second Intifada, when he was captured, convicted, and imprisoned by Israel on charges of involvement in deadly attacks. Barghouti declined to recognise the legitimacy of the court or enter a plea, but stated that he had no connection to the incidents for which he was convicted.[3] An Inter-Parliamentary Union report, considered the most detailed independent review of the trial, found that Barghouti was not given a fair trial and questioned the quality of the evidence.[4][5]

Several prominent supporters of a resumption of the Israel-Palestine peace process view Barghouti as the leader most able to unify the Palestinians and negotiate a compromise with Israel. He has been referred to as "the Palestinian Mandela,".[6][7][8][9]

During his years in prison, Barghouti has continued to be politically active. He was an instigator and lead author of the 2006 Palestinian Prisoners’ Document, which proposed a political path to a two-state solution, and secured support from Hamas. He has organised education for fellow inmates, and in 2017 led a hunger strike that led to increased visitation rights.[10] Since October 2023, he has had been denied visits from his family and been severely beaten several times, leading to persistent damage to his health, according to his lawyer.[11] Israeli authorities have rejected his complaints over the incidents. Several attempts to secure his release through negotiations have failed.[12]

Early life, education and expulsion

Barghouti was born in the village of Kobar near Ramallah in the West Bank. Like his distant cousin Mustafa Barghouti, a fellow Palestinian political leader, he belongs to the extended Barghouti family. His younger brother Muqbel described him as "a naughty and rebellious boy".[13]

In 1967, when Barghouti was seven-years-old, Israel launched a war against Egypt and Syria and occupied the West Bank. According to The Economist, Marwan’s “neighbours were beaten up or arrested for flying Palestinian flags. Military bases and Jewish settlements sprang up around their village. Israeli soldiers shot dead the family dog for barking,".[12]

Barghouti joined Fatah at age 15,[2] and he was a co-founder of the Fatah Youth Movement (Shabiba) on the West Bank. That year he was first imprisoned by Israel.[14] At 18, he was imprisoned again. In The New York Times he wrote that during interrogation, he was forced to strip naked, spread his legs, and was struck on the genitals so hard that he lost consciousness.[14] He completed his secondary education and received a high school diploma while serving a four-year term in jail, where he became fluent in Hebrew.[15]

Barghouti enrolled at Birzeit University in 1983, though arrest and exile meant that he did not receive his Bachelor's degree (History and Political Science) until 1994. He earned a Master's in International Relations, also from Birzeit , in 1998. As an undergraduate, he was active in student politics on behalf of Fatah and headed the Birzeit Student Council. In 1984, he married Fadwa Ibrahim, a fellow student. Fadwa studied law and was a prominent advocate in her own right on behalf of Palestinian prisoners, before becoming the leading campaigner for her husband's release from his current jail term. Together the couple had four children. Before his eldest son was born, and while still a student leader, Barghouti was jailed for a third time.[12] He missed the birth of his eldest son.[14] In May 1987, Israel expelled him. Initially Barghouti and Fadwa moved to Tunis, and then in April 1988 to Amman.

First Intifada, the Oslo Accords and the aftermath

From exile, during the First Intifada, Barghouti continued to maintain contacts among activists in the West Bank. He simultaneously built relationships with the older generation of Fatah activists, who had waged their struggle from exile for more than three decades. He was elected to Fatah’s Revolutionary Council, the movement’s internal parliament, in 1989.[16] When he was allowed to return to Palestine in April 1994 as a result of the Oslo Accords, Barghouti found that he was able to bridge the divide between the two groups.[15]

Although he was a strong supporter of the peace process, he doubted that Israel was committed to it.[2] In 1996, he was elected to the Palestinian Legislative Council for the district of Ramallah.[2] Barghouti campaigned against corruption in Arafat's administration and human rights violations by its security services.[2] He participated in diplomacy and built relationships with a number of Israeli politicians, and with leaders of Israel’s peace movement. A series of peace conferences in the wake of the Oslo accords featured “heated discussions,”.[16] When Meir Shitreet fell ill during a peace conference in Italy, Shitreet said that Barghouti sat at his bedside through the night.[12] In 1998 he attended a meeting with members of the Israeli Knesset, referring to those present as friends, and calling to “strengthen this peace process,".[5] Haim Oron, a former Israeli cabinet minister, recalled that “he spoke about the right of the Palestinians, and when I spoke about the right of Jews, he understood,".[12] His assistant has claimed that Barghouti never refused to meet any Israeli.[12] By the late 1990s, Palestinians had become frustrated with the lack of progress toward an independent state that they felt had been promised by the Oslo accords, and by the privations of life under occupation. There were frequent demonstrations by civil society and political groups. According to Diana Buttu, “Marwan was somebody who was present at each and every protest for weeks and weeks and weeks on end. It became very clear that we were just never going to see freedom,".[5] Barghouti met with the central committees of almost every Israeli party, the journalist Gideon Levy has claimed, to warn them that, with an impasse in the peace process, the situation was tending toward violence.[5]

The formal position occupied by Barghouti was Secretary-General of Fatah in the West Bank.[17] By the summer of 2000, particularly after the Camp David summit failed, Barghouti was disillusioned and said that popular protests and "new forms of military struggle" would be features of the "next Intifada".[2][15]

Second Intifada

Outbreak of Second Intifada and political leadership

In September 2000, the Second Intifada began. Barghouti became increasingly popular as a leader of demonstrations, as a spokesperson for Palestinian interests, and as leader of the Tanzim, a grouping of younger activists within Fatah who had taken up arms. Barghouti described himself as “a politician, not a military man,".[13] Barghouti led marches to Israeli checkpoints, where riots broke out against Israeli soldiers and spurred on Palestinians in speeches at funerals and demonstrations, advocating the use of force to expel Israel from the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[2] He has stated that, "I, and the Fatah movement to which I belong, strongly oppose attacks and the targeting of civilians inside Israel, our future neighbor, I reserve the right to protect myself, to resist the Israeli occupation of my country and to fight for my freedom" and has said, "I still seek peaceful coexistence between the equal and independent countries of Israel and Palestine based on full withdrawal from Palestinian territories occupied in 1967."[18]

As the Palestinian death toll in the Second Intifada mounted, Barghouti called for Palestinians to target Israeli soldiers and settlers in the West Bank and Gaza, but not within Israel.[15][19] Others, such as leaders of Hamas, openly backed attacks on civilians within Israel. Israel has accused Barghouti of having co-founded and lead the Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades during this period, which he has denied.[2]

Israel attempted to assassinate him in 2001.[1] That August, Israeli forces fired two missiles from an illegal West Bank settlement at a convoy of cars in Ramallah and injured Barghouti’s bodyguard.[20] At the time, Israeli security sources claimed that they had intended to kill another Fatah operative. The then-head of Shin Bet subsequently claimed to have made two attempts to assassinate Barghouti.[21] Barghouti went into hiding.

Israeli arrest, interrogation and trial

Barghouti was captured on 15 April 2002 by Israeli soldiers, who had disguised their journey to his location by hiding in a civilian ambulance.[22] He was transferred to the Moscovia Detention Centre. On 18 April, Barghouti was reported to have declined to cooperate with his interrogators, and allowed to communicate freely with his lawyer. He was then denied the right to see his lawyer for the next month, except for an occasion on which they were not allowed to discuss the investigation.[4] The next time he was able to talk freely with his lawyer, Barghouti described having been subject to severe sleep deprivation and insufficient food. He described the torture, in the form of the shabeh method, in a later book, 1000 Days In Solitary Jail.[23] He said that he was forced to sit on a chair with nails protuding into his back for hours at a time..[23] Simon Foreman, the lawyer commissioned by the Inter-Parliamentary Union to report on the trial, has said “the witnesses whose statements were used to accuse [Barghouti], many of them made the same kind of statements and those allegations were disregarded, openly disregarded by the courts,".[4][5] Barghouti has also stated that the interrogators threatened to kill him and his eldest son.[4] He has written that during his pre-trial detention, in addition to Moscovia, he was held for periods at Camp 1391 and the Petah Tikva prison.[23]

Charges, verdict and sentences

Israel filed its indictment on 14 August and Barghouti’s trial commenced on 5 September.[24] Barghouti was charged with 26 charges of murder and attempted murder stemming from attacks carried out by the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades on Israeli civilians and soldiers.[25][26] Barghouti refused to present a defense to the charges brought against him, maintaining throughout that the trial was illegal and illegitimate.[27] He stressed that he supported armed resistance to the Israeli occupation, but condemned attacks on civilians inside Israel. According to the case argued by Israel at his trial, he had supported and authorized such attacks. On 20 May 2004, he was convicted of five counts of murder: authorizing and organizing the murder of Georgios Tsibouktzakis (aka Father Germanos, a Greek Orthodox monk-priest), a shooting adjacent to Giv'at Ze'ev in which a civilian was killed, and the Seafood Market attack in Tel Aviv in which three civilians were killed. In addition, he was convicted of attempted murder for a failed car bomb attack near Malha Mall that exploded prematurely, resulting in the deaths of two suicide bombers, and for membership and activity in a terrorist organization. He was acquitted of 21 counts of murder in 33 other attacks as no proof was brought to link Barghouti directly with the specific decisions of the local leadership of the Tanzim to carry out these particular attacks.[28] Following the verdict, Barghouti shouted in Hebrew, "This is a court of occupation that I do not recognize. A day will come when you will be ashamed of these accusations. I have no more connection to these charges than you, the judges, do,".[29] On 6 June 2004, he was sentenced to the maximum possible punishment for his convictions: five cumulative life sentences for the murders and an additional 40 years, consisting of 20 years each for attempted murder and for membership and activity in a terrorist organization. The Israeli verdict against him in effect removed Arafat's only political rival.[30]

Criticism of trial

In the most detailed third party report on the case, the Inter-Parliamentary Union found that the “numerous breaches of international law” to which Barghouti was subjected “make it impossible to conclude that Mr. Barghouti was given a fair trial,”.[4][31]. The criticisms raised by Simon Foreman, the report’s author, included the court’s failure to consider the public allegations of torture; its authorisation of incommunicado detention; prejudicial statements by the presiding judge; the transportation of Barghouti to Israel contrary to the Fourth Geneva Convention; and the poor evidence for guilt.[4] Foreman wrote, "According to the prosecution, only 21 of the prosecution witnesses were actually in a position to testify directly regarding Mr. Barghouti's role in these attacks. But none of these 21 individuals in fact accused him. About 12 of them explicitly told the court that he was not involved,".[4] Concerning "material" evidence, Barghouti’s lawyer told Foreman that “no document originated by Mr. Barghouti had implicated him in the acts of which he was being accused,”.[4]

Campaign for release and prisoner-swap negotiations

The International Campaign to Free Marwan Barghouti and All Palestinian Prisoners was launched in 2013 from Nelson Mandela’s former cell on Robben Island.[32] The campaign was launched by Fadwa and Ahmed Kathrada, who was jailed alongside Mandela at the Rivonia Trial. Barghouti has often drawn comparisons to Mandela from commentators inclined toward a resumption of the peace process.[7][8][33] For example, Reuters reported that some see Barghouti "as a Palestinian Nelson Mandela, the man who could galvanize a drifting and divided national movement if only he were set free by Israel". Many of his supporters have campaigned for his release. They include prominent Palestinian figures, members of European Parliament and the Israeli group Gush Shalom. According to The Jerusalem Post, "[u]nlike many in the Western media, Palestinian journalists have rarely referred to Barghouti in these terms.[34] In August 2023, Barghouti's wife Fadwa held meetings with senior officials and diplomats across the world, including Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi, to advocate for her husband's release and position him as a successor to Abbas. According to Al-Sharq al-Awsat, Barghouti would run in Palestinian presidential elections and maintained a polling lead over all other candidates.

In August 2023, Fadwa held meetings with senior officials and diplomats across the world, including Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi, to advocate for her husband's release and position him as a successor to Abbas. According to Al-Sharq al-Awsat, Barghouti would run in Palestinian presidential elections and maintained a polling lead over all other candidates.[35]

The Israeli debate on whether to free Barghouti

In 2008, 45% of Israelis supported the release of Barghouti, while 51% were opposed.[36] Another approach is to suggest that Israel's freeing of Barghouti would be an excellent show of good faith in the peace process. Some prominent Israelis have called for Barghouti’s release, citing his unique ability to unite Palestinians These include Ami Ayalon,[37][38] Efraim Halevy,[39][40] Meir Shitreet,[12] and both Yossi Beilin[5] and Haim Oron[12], two former ministers on the left of Israeli politics.[6] Several IDF officers involved in Barghouti’s 2002 capture have taken a similar view.[21]

Every Israeli administration since Barghouti’s imprisonment has declined to release him. Ayalon claimed in 2024 that “You will not find anybody in our current political community that has any interest in releasing Marwan Barghouti,".[41] Figures who have spoken in opposition to his release include former Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon, Avi Dichter, and former Foreign Minister Silvan Shalom, who called Barghouti “an assassin who has blood on his hands,”.[21][42][43]

This view gained popularity among the Israeli left after the 2005 disengagement from the Gaza Strip. Still others, operating from a realpolitik perspective, have pointed out that allowing Barghouti to re-enter Palestinian politics could serve to bolster Fatah against gains in Hamas' popularity.[44] According to Pinhas Inbari of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs,

"Hamas understands it needs to provide its supporters with some comfort, especially seeing the suffering of the Palestinian people. For this reason, Hamas is willing to accept Barghouti's release and to deal with him after he is free. Without the severe state of the Palestinian people, Hamas would object to the release of Barghouti."[45]

In January 2007, Israeli Deputy Prime Minister Shimon Peres declared that he would pardon Barghouti if elected president.[43] Peres was elected, but issued no pardon.

History of negotiations concerning Barghouti’s release

In 2004, Israel’s ambassador to Washington Danny Ayalon proposed, with the “tacit agreement” of Ariel Sharon, that Israel would free Barghouti in exchange for the Israeli spy Jonathan Pollard, who was imprisoned by the United States. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice rejected the request.[21] In 2006, there were conflicting claims concerning proposals for Barghouti’s release. A Saudi newspaper reported that Condoleezza Rice had proposed such a step to Israel, with no mention of a quid pro quo, but Ehud Olmert denied that the idea had been raised in talks with the United States.[46] He reportedly continued to oppose Barghouti’s release in 2007.[47]

Hamas sought the inclusion of Barghouti in the 2011 prisoner exchange deal that led to the release of Gilad Shalit, but Israel refused to include him.[21]

During the prisoner swap negotiations in 2024 and 2025 that arose from the Gaza War, Hamas said that Barghouti was at the top of their list of prisoners whom they wanted Israel to free.[48] Israel again refused.[49] The Economist reported that Mahmoud Abbas, who was expected to face a political challenge from Barghouti on the latter’s release, “urged Qatari mediators to remove Barghouti’s name from the list of prisoner exchanges,"[49]. In January 2025 an Israeli government official denied reports that Barghouti was set to be released and exiled to Turkey.[50]

Political activity in prison

2005 and 2006 Palestinian elections and disputes with Fatah

Yasser Arafat died in November 2004, and the Palestinian Authority called a presidential election for January 2005. Barghouti announced from his isolation cell that he would contest the election, challenging interim-President Mahmoud Abbas, a long-time Fadwa administrator of Arafat’s generation. Fadwa registered her husband’s candidacy as an independent on 1 December.[51][52]

The Israeli government came to know that two of Barghouti’s closest confidantes – Fadwa and advisor Qadura Fares – privately opposed Barghouti’s decision to stand, and decided to allow the two to meet with Barghouti to press their case, breaking two years in which he had been denied such contact.[21] His candidacy was also criticised by Fatah leaders as a threat to the movement’s unity.[53][54] His campaign manager announced Barghouti’s decision to withdraw from the race on 12 December. In a letter read at the announcement, Barghouti accused Fatah’s leadership of having grown “old, weak and alienated” from the rank and file.[55] In 2016, Fares said that he believed his advice had been a mistake.[21]

Abbas won the election, and there has been no Palestinian presidential election since.

In 2006 Israeli media reported that MK Haim Oron had met with Barghouti in prison dozens of times, and had carried messages back and forth between Barghouti and Prime Minister Ehud Olmert.[46] Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni also met directly with Barghouti.

Split from Fatah

On 14 December 2005, Barghouti announced that he had formed a new political party, al-Mustaqbal ("The Future"), mainly composed of members of Fatah's "Young Guard", who repeatedly expressed frustration with the entrenched corruption in the party. The list, which was presented to the Palestinian Authority's central elections committee on that day, included Mohammed Dahlan, Qadura Fares, Samir Mashharawi and Jibril Rajoub.[27]

The split followed Barghouti's earlier refusal of Mahmoud Abbas' offer to be second on the Fatah party's parliamentary list, behind Palestinian Prime Minister Ahmed Qurei. Barghouti had actually topped the list,[56] but this had not become apparent until after the new party had been registered.

Reactions to the news were split. Some suggested that the move was a positive step towards peace, as Barghouti's new party could help reform major problems in Palestinian government. Others raised concern that it could wind up splitting the Fatah vote, inadvertently helping Hamas. Barghouti's supporters argued that al-Mustaqbal would split the votes of both parties, both from disenchanted Fatah members as well as moderate Hamas voters who do not agree with Hamas' political goals, but rather its social work and hard position on corruption. Some observers also hypothesized that the formation of al-Mustaqbal was mostly a negotiating tactic to get members of the Young Guard into higher positions of power within Fatah and its electoral list.

Barghouti eventually was convinced that the idea of leading a new party, especially one that was created by splitting from Fatah, would be unrealistic while he was still in prison. Instead he stood as a Fatah candidate in the January 2006 PLC elections, comfortably regaining his seat in the Palestinian Parliament.

Prisoners’ Document and other activism

On 11 May 2006, Palestinian leaders held in Israeli prisons released the National Conciliation Document of the Prisoners. The document was a proposal initiated by Marwan Barghouti and leaders of Hamas, the PFLP, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad and the DFLP that proposed a basis upon which a coalition government should be formed in the Palestinian Legislative Council. This came as a result of the political stalemate in the Palestinian territories that followed Hamas' election to the PLC in January 2006. Crucially, the document also called for negotiation with the state of Israel in order to achieve lasting peace. The document quickly gained popular currency and is now considered the bedrock upon which a national unity government should be achieved. According to Haaretz, Barghouti, although not officially represented in the negotiations of a Palestinian unity government in February 2007, played a major role in mediating between Hamas and Fatah and formulating the compromise reached on 8 February 2007.[57] In 2009, he was elected to party leadership at the Fatah Conference in Bethlehem.[58]

Barghouti declined to testify before an Israeli court in January 2012, but used the opportunity of his appearance to say that “an Israeli withdrawal to the 1967 lines and the establishment of a Palestinian state will bring an end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” according to Haaretz’s Avi Issacharoff.[59] That March, in a letter from prison, Barghouti called for a new wave of civil resistance against the occupation, and for the Palestinian Authority to end all coordination with Israel. He wrote “Large-scale popular resistance at this stage serves the cause of our people,”.[60]

In November 2014, months after more than 2,000 Palestinians were killed by Israel in the 2014 Gaza War, Barghouti urged the Palestinian Authority to end security cooperation with Israel and called for a Third Intifada against Israel.[61] In 2016, a plan for confronting the occupation, purportedly authored by Barghouti and smuggled from prison, was presented by an ally. The plans hinged on “mass disobedience” and demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of people according to the Economist’s 1843 Magazine.[12] Barghouti expected that Israel would kill some of the demonstrators.

2017 hunger strike

In April 2017 he organized a hunger strike of Palestinian security prisoners in Israeli jails.[62] In an op-ed for the The New York Times, Barghouti said that the hunger strikers sought to end the “torture, inhumane and degrading treatment, and medical negligence” to which prisoners were subject..[14] A list of demands issued by the strikers included access to telephones to communicate with their families, increased visitation rights, and a series of steps to address medical negligence.[63] They also included access to books and newspapers and an end to the practices of solitary confinement and administrative detention.

On 7 May, the Israel Prison Service released videos allegedly showing Barghouti hiding in the toilet stall of his cell while eating cookies and candy, then trying to flush the wrappers. The videos were recorded on 27 April and on 5 May, a period during which almost 1,000 of Barghouti's fellow prisoners were refusing all food.[64][65] Anonymous sources in the prison service confirmed the authenticity of the videos, saying that the food was made available to Barghouti to test his adherence to the hunger strike. Barghouti's attorney refused to respond to the videos, while his wife claimed that they had been "fabricated" to discredit him. Israeli media reported that this was not Barghouti's first time being caught secretly breaking a hunger strike, and that in 2004 he had been photographed hiding a plate after eating off it in his cell.[66][67][68] According to Haaretz’s Amos Harel, among Palestinians, the episode “only strengthened his image as a leader who is feared by Israel – which resorts to ugly tricks in order to trip him up,".[69] The hunger strike ended after Israel conceded a second family visit for each prisoner per month.[10]

Subsequent activism and continued popularity

Barghouti intended to contest the Palestinian Presidential elections slated for 2021,[70] but they were cancelled by President Abbas, citing Israel’s refusal to permit voting in East Jerusalem. but they were cancelled by President Abbas, citing Israel’s refusal to permit voting in East Jerusalem.[71] Immediately prior to the cancelation, a poll suggested that Barghouti would go on to win the Presidency, with more than double Abbas’s support, and significantly more than that of Ismail Haniyeh.[72] Barghouti remains the most popular Palestinian leader. In each of the five polls conducted by the Palestinian Centre for Policy and Survey Research between September 2023 and September 2024, Barghouti came out ahead of a Hamas candidate when Palestinians were asked who they would vote for as President in a two-way race.[73] There has been no Palestinian Presidential election since 2005.

Conditions of imprisonment and alleged mistreatment

Barghouti was held in solitary confinement for three years following his 2002 detention and has frequently been returned to solitary confinement since.[74] Since 7 October 2023, Barghouti has been interred in solitary confinement. Shortly after that date, the governor of Ofer Prison ordered Barghouti to kneel before the governor, according to his son, Arab Barghouti.[75] Arab described the order as an attempt to humiliate Barghouti, and by extension the watching prisoners, who saw Barghouti as a leader. Arab added that when his father refused to comply he was forced to his knees by prison guards, dislocating his shoulder.

In December 2023, his lawyer claimed, Barghouti was beaten on several occasions, and on one occasion “dragged on the floor naked in front of other prisoners.[76] In March 2024, Barghouti told his lawyers that he was dragged to an area of Megiddo prison without security cameras and assaulted with batons by prison guards.[76][77] The Guardian reported, "He recalled bleeding from the nose as he was dragged across the floor by his handcuffs, before he was beaten unconscious,".[76] According to his family, speaking in February 2024, Barghouti was held in the dark, with loud music playing into his cell for days at a time.[78] In May 2024, The Guardian reported that Barghouti “spends his days huddled in a cramped, dark, solitary cell, with no way to tend to his wounds, and a shoulder injury from being dragged with his hands cuffed behind his back,”.[76] The Public Committee Against Torture in Israel said that Barghouti had been subjected to treatment amounting to torture, which they said had “become standard across all detention facilities since 7 October,”.[9]

Israeli prison authorities were accused of “brutally assaulting” Barghouti in September 2024.[77] The Israeli prison service said in October 2024 that they had rejected two complaints of mistreatment by Barghouti over the past year on the grounds that there had been no violation of the law.[11]

Personal life

On 21 October 1984, Barghouti married Fadwa Barghouti.[79]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Marwan Barghouti". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Profile: Marwan Barghouti". BBC News. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ Shulman, Robin (21 May 2004). "Palestinian Leader Convicted in Israel". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Foreman, Simon (3 October 2003). "The trial of Mr. Marwan Barghouti". Inter-Parliamentary Union. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Scott, Georgia; Scott, Sophia (20 June 2022), Tomorrow's Freedom (Documentary), Cocoonfilms, Groundtruth Productions, retrieved 23 March 2025

- ^ "Opinion | In Israel and Gaza, Biden Needs to Do More to Build Peace -…". archive.is. 12 November 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b "Can Marwan Barghouti, the 'Palestinian Mandela', bring peace to Gaza?". France 24. 4 November 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b Goat, Elliott; published, The Week UK (6 February 2024). "Marwan Barghouti: the Palestinian hostage 'seen as Nelson Mandela'". theweek. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b Staff, Al Jazeera. "Will Israel release Marwan Barghouti, the 'Palestinian Mandela'?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b Beaumont, Peter (27 May 2017). "Mass Palestinian hunger strike in Israeli jails ends after visitation deal". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b France-Presse, Agence (28 October 2024). "Israeli prison staff accused of assaulting Marwan Barghouti". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Marwan Barghouti, the world's most important prisoner". archive.is. 22 July 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b Bennet, James (19 November 2004). "Jailed in Israel, Palestinian Symbol Eyes Top Post". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Barghouti, Marwan (16 April 2017). "Why We Are on Hunger Strike in Israel's Prisons". New York Times. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Hajjar, Lisa (2006). "Competing Political Cultures: Interview with Marwan Barghouti". In Beinin, Joel; Stein, Rebecca L. (eds.). The Struggle for Sovereignty: Palestine and Israel, 1993-2005. Stanford University Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0-8047-5365-4.

- ^ a b "הראיון בו שרטט ברגותי את מתווה אינתיפאדת אל-אקצא - המרכז הירושלמי לענ…". archive.is. 28 February 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Kelly, Tobias (December 2006). Cambridge Studies in Law and Society: Law, Violence and Sovereignty Among West Bank Palestinians. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780521868068.

- ^ Barghouti, Marwan (16 January 2002). "Want Security? End the Occupation". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Sher, Gilead (2006). The Israeli-Palestinian Peace Negotiations, 1999-2001: Within Reach. Taylor & Francis. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-7146-8542-7.

- ^ Goldenberg, Suzanne; Quirke, Virginia; Jerusalem (5 August 2001). "Israel tries to kill top Arafat aide in missile attack on car". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weitz, Gidi. "Will Marwan Barghouti be the Palestinian Nelson Mandela?". Haaretz.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ גורמי ביטחון: ברגותי מפגין יהירות בחקירה. Haaretz (in Hebrew). 18 April 2002. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Barghūthī, Marwān (2011). Alf yawm fī zinzānat al-ʻazl al-infirādī (al-Ṭabʻah 1 ed.). Bayrūt: al-Dār al-ʻArabīyah lil-ʻUlūm Nāshirūn. ISBN 978-614-01-0123-4. OCLC 702137879.

- ^ "Human rights of parliamentarians: The trial of Mr. Marwan Barghouti - Palestine". archive.ipu.org. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "State of Israel vs. Marwan Barghouti: Ruling by Judge Zvi Gurfinkel". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 12 December 2002. Archived from the original on 5 July 2004.

- ^ "Marwan Barghouti Indictment". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 14 August 2002. Archived from the original on 5 July 2004. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Barghouti, Marwan". MEDEA. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Bergerfreund, Assaf (21 May 2004). "Barghouti Found Guilty of 5 Murders". Haaretz. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "CNN.com - Israel court convicts Fatah leader of murder - May 20, 2004". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Shindler, Colin (2013). A History of Modern Israel. Cambridge University Press. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-107-02862-3.

- ^ The Inter-Parliamentary Union report is widely cited, including:

- "A Cynical Ploy by Tel Aviv". Morning Star. 28 April 2017. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Ebrahim, Shannon (27 October 2013). "Palestine's Mandela". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- Hammond, Jeremy R. (12 May 2017). "The Prejudice Against Barghouti". Al-Ahram Weekly. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Zogby, James (22 April 2017). "Punishment of Barghouti Will Not End Protests". The National. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Why We Are on Hunger Strike in Israel's Prisons - The New York Times". archive.is. 18 April 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Marwan Barghouti: Peace talks with Israel have failed". Haaretz. Reuters. 19 November 2009. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009.

- ^ Abu Toameh, Khaled (26 November 2009). "Analysis: Marwan Barghouti - A Nelson Mandela or a PR gimmick?". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Zboun, Kifah (2 August 2023). "Barghouti's Wife Leads Movement to Support Him as Possible Successor to Abbas". Al-Sharq al-Awsat. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ "Joint Israeli-Palestinian Public Opinion Poll". Foundation Office Palestinian Territories. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Graham-Harrison, Emma; Kierszenbaum, Quique (14 January 2024). "Ex-Shin Bet head says Israel should negotiate with jailed intifada leader". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Barghouti, Marwan (January 2011). "Message from a Palestinian prisoner". Race & Class. 52 (3): 50–53. doi:10.1177/0306396810389252. ISSN 0306-3968.

- ^ Karpel, Dalia. "A former spy chief is calling on Israelis to revolt". Haaretz.com. Archived from the original on 13 November 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Many Palestinians Pin Postwar Hopes on Leader Jailed by Israel for Tw…". archive.is. 6 July 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Many Palestinians Pin Postwar Hopes on Leader Jailed by Israel for Tw…". archive.is. 6 July 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Ben Gedalyahu, Tzvi (25 January 2006). "Barghouti´s Popularity Spurs Campaign to Free Him". Arutz Sheva. Archived from the original on 21 March 2006. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Israelis may release jailed Fatah leader". The Daily Star. 28 November 2005. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "The Blame Game". The Forward. 31 October 2003. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Inbari, Pinhas (20 December 2007). על סיכויי השחרור של גלעד שליט [On the chances of the release of Gilad Shalit] (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 24 December 2007.

- ^ a b "חדשות - פוליטי/מדיני nrg - לבני וברגותי נפגשו בכלא הדרים". www.makorrishon.co.il. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "אולמרט נגד שחרור ברגותי". www.inn.co.il. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Marwan Barghouti: Jailed Palestinian murderer may hold key to Gaza ce…". archive.is. 6 March 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b Rasha Jalal ــ Gaza. "Will Gaza ceasefire's 2nd phase fail over prominent prisoners?". The New Arab. Archived from the original on 12 March 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Milshtein, Dr Michael (3 January 2025). "The Prisoner's Dilemma: The question of Marwan Barghouti". Ynetnews. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ McGreal, Chris (2 December 2004). "Crucial choice on path to statehood". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Imprisoned Palestinian Enters Presidential Race - The New York Times". archive.is. 6 March 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Ellingwood, Ken (13 December 2004). "PLO's Barghouti Ends Candidacy for President". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Murphy, Maureen Clare (16 December 2004). ""Message received": Hatem Abdel Qader on Barghouti's presidential election withdrawal". The Electronic Intifada. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "CNN.com - Jailed Barghouti quits Palestinian leadership race - Dec 12, 2004". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Fatah splits before key election". BBC News. 15 December 2005. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Issacharoff, Avi (9 February 2007). "From behind the bars". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007.

- ^ "Labor minister: Israel must consider freeing Fatah victor Barghouti". Haaretz. Reuters. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Issacharoff, Avi (26 January 2012). "In Rare Court Appearance, Marwan Barghouti Calls for a Peace Deal Based on 1967 Lines". Haaretz. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Jailed Palestinian leader Barghouti urges resistance". BBC News. 27 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Bacchi, Umberto (11 November 2014). "Jailed Palestinian Leader Marwan Barghouti Calls for Third Intifada Against Israel". International Business Times UK. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Hunger strike puts jailed Palestinian in spotlight". Fox News. Associated Press. 21 April 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "On seventh day: Mass hunger strike continues despite escalation". www.addameer.org. 23 April 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Palestinian hunger strike leader Barghouti 'filmed eating'". BBC. 8 May 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Did hunger striking Palestinian prisoner Barghouti just eat some cookies? Israel says he did". The Washington Post. 8 May 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Kubovich, Yaniv; Khoury, Jack (8 May 2017). "Israel Releases Footage of Palestinian Hunger Strike Leader Barghouti Eating in His Prison Cell". Haaretz. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Levy, Elior (8 May 2017). "Barghouti's wife: 'Recordings of Marwan breaking the strike are fake'". Ynetnews. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Prisons Official Admits: We Lured Hunger Striking Barghouti with Candy". Jewish News Service. 8 May 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ "Israel Averts One Crisis With End of Palestinian Prisoners' Hunger St…". archive.is. 11 January 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Bishara, Marwan. "Palestinian political prisoner Marwan Barghouti for president?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Palestinian leader delays parliamentary and presidential elections, b…". archive.is. 7 February 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Public Opinion Poll No (79) | PCPSR". pcpsr.org. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Press Release: Public Opinion Poll No (93) | PCPSR". www.pcpsr.org. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Ashly, Jaclynn. "The love story of Fadwa and Marwan Barghouti". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Zeteo (18 January 2025). The Case of Marwan Barghouti: How Israel Imprisoned Palestine’s Most Popular Leader. Retrieved 23 March 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d Michaelson, Ruth; Taha, Sufian; Kierszenbaum, Quique (18 May 2024). "Israeli abuse of jailed Palestinian leader Marwan Barghouti 'amounts to torture'". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b Khoury, Jack. "Jailed Palestinian leader Marwan Barghouti 'beaten with clubs' by guards, family claims". Haaretz.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Marwan Barghouti: Jailed Palestinian murderer may hold key to Gaza ce…". archive.is. 6 March 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Who is Marwan Barghouti, 'Palestinian Mandela' who could bring peace to Gaza?". Firstpost. 15 January 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

Further reading

- Interview with Marwan Barghouti. "Competing Political Cultures". In: Beinin, Joel; Stein, Rebecca L. (eds) (2006). The Struggle for Sovereignty: Palestine and Israel, 1993-2005. Stanford University Press. pp. 105–111.

- Pratt, David (2006). Intifada: The Long Day of Rage. Casemate. First published by Sunday Herald Books.

- Haddad, Toufic. "Changing the Rules of the Game: A Conversation with Marwan Barghouti, Secretary-General of Fateh in the West Bank". In: Honig-Parnass, Tikva; Haddad, Toufic. (eds) (2007). Between the Lines: Readings on Israel, the Palestinians, and the U.S. "War on Terror". Haymarket Books. pp. 65–69.

External links

- Ramzy Baroud, What Marwan Barghouti Really Means to Palestinians, Palestine Chronicle, 4 April 2012

- Bitter Circus Erupts as Israel Indicts a Top Fatah Figure, The New York Times, 15 August 2002

- The 'Palestinian Napoleon' Behind Mideast Cease-fire, CS Monitor, July 3, 2003.

- Uri Avnery, "Palestine's Mandela" Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, New Internationalist, November 2007

- Israel's Ministry of Foreign Affairs page about Barghouti

- 1959 births

- Living people

- Birzeit University alumni

- Central Committee of Fatah members

- Fatah military commanders

- Members of the 1996 Palestinian Legislative Council

- Members of the 2006 Palestinian Legislative Council

- Palestinian hunger strikers

- Palestinian people convicted of murder

- Palestinian people imprisoned by Israel

- Palestinian prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Palestinianists

- People convicted of murder by Israel

- People convicted on terrorism charges

- People from Ramallah

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Israel

- People of the Second Intifada